Getty Images

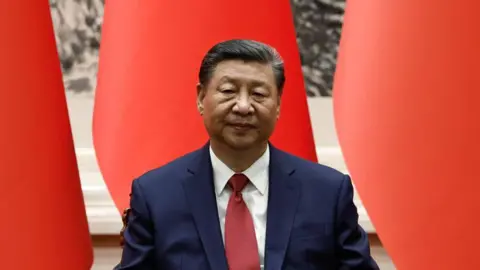

Getty ImagesThe People’s Republic of China has a “magic weapon”, according to its founding leader Mao Zedong and its current president Xi Jinping.

It is called the United Front Work Department – and it is raising as much alarm in the West as Beijing’s growing military arsenal.

Yang Tengbo, a prominent businessman who has been linked to Prince Andrew, is the latest overseas Chinese citizen to be scrutinised – and sanctioned – for his links to the UFWD.

The existence of the department is far from a secret. A decades-old and well-documented arm of the Chinese Communist Party, it has been mired in controversy before. Investigators from the US to Australia have cited the UFWD in multiple espionage cases, often accusing Beijing of using it for foriegn interference.

Beijing has denied all espionage allegations, calling them ludicrous.

So what is the UFWD and what does it do?

‘Controlling China’s message’

The United Front – originally referring to a broad communist alliance – was once hailed by Mao as the key to the Communist Party’s triumph in the decades-long Chinese Civil War.

After the war ended in 1949 and the party began ruling China, United Front activities took a backseat to other priorities. But in the last decade under Xi, the United Front has seen a renaissance of sorts.

Xi’s version of the United Front is broadly consistent with earlier incarnations: to “build the broadest possible coalition with all social forces that are relevant”, according to Mareike Ohlberg, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund.

On the face of it, the UFWD is not shadowy – it even has a website and reports many of its activities on it. But the extent of its work – and its reach – is less clear.

While a large part of that work is domestic, Dr Ohlberg said, “a key target that has been defined for United Front work is overseas Chinese”.

Today, the UFWD seeks to influence public discussions about sensitive issues ranging from Taiwan – which China claims as its territory – to the suppression of ethnic minorities in Tibet and Xinjiang.

It also tries to shape narratives about China in foreign media, target Chinese government critics abroad and co-opt influential overseas Chinese figures.

“United Front work can include espionage but [it] is broader than espionage,” Audrye Wong, assistant professor of politics at the University of Southern California, tells the BBC.

“Beyond the act of acquiring covert information from a foreign government, United Front activities centre on the broader mobilisation of overseas Chinese,” she said, adding that China is “unique in the scale and scope” of such influence activities.

Reuters

ReutersChina has always had the ambition for such influence, but it’s rise in recent decades has given Beijing the ability to exercise it.

Since Xi became president in 2012, he has been especially proactive in crafting China’s message to the world, enouraging a confrontational “wolf warrior” approach to diplomacy and urging his country’s diaspora to “tell China’s story well”.

The UFWD operates through various overseas Chinese community organisations, which have vigorously defended the Communist Party beyond its shores. They have censored anti-CCP artwork and protested at the activities of Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama. The UFWD has also been linked to threats against members of persecuted minorities abroad, such as Tibetans and Uyghurs.

But much of the UFWD’s work overlaps with other party agencies, operating under what observers have described as “plausible deniability”.

It is this murkiness that is causing so much suspicion and apprehension about the UFWD.

When Yang appealed against his ban from the UK amid espionage allegations, an immigration court ruled that he had downplayed his ties with the UFWD. UK officials allege he leveraged his relationships with influential British figures for Chinese state interference.

Yang, however, maintains that he has not done anything unlawful and that the spy allegations are “entirely untrue”.

Supplied

SuppliedCases like Yang’s are becoming increasingly common. In 2022, British Chinese lawyer Christine Lee was accused by the MI5 of acting through the UFWD to cultivate relationships with influential people in the UK. The following year, Liang Litang, a US citizen who ran a Chinese restaurant in Boston, was indicted for providing information about Chinese dissidents in the area to his contacts in the UFWD.

And in September, Linda Sun, a former aide in the New York governor’s office, was charged with using her position to serve Chinese government interests – receiving benefits, including travel, in return. According to Chinese state media reports, she had met a top UFWD official in 2017, who told her to “be an ambassador of Sino-American friendship”.

It is not uncommon for prominent and successful Chinese people to be associated with the party, whose approval they often need, especially in the business world.

But where is the line between peddling influence and espionage?

“The boundary between influence and espionage is blurry” when it comes to Beijing’s operations, said Ho-fung Hung, a politics professor at Johns Hopkins University.

This ambiguity has intensified after China passed a law in 2017 mandating Chinese nationals and companies to co-operate with intelligence probes, including sharing information with the Chinese government – a move that Dr Hung said “effectively turns everyone into potential spies”.

The Ministry of State Security has released dramatic propaganda videos warning the public that foreign spies are everywhere and “they are cunning and sneaky “.

Some students who were sent on special trips abroad were told by their universities to limit contact with foreigners and were asked for a report of their activities on their return.

And yet Xi is keen to promote China to the world. So he has tasked a trusted arm of the party to project strength abroad.

And that is becoming a challenge for Western powers – how do they balance doing business with the world’s second-largest economy alongside serious security concerns?

Wrestling with the long arm of Beijing

Genuine fears over China’s overseas influence are playing into more hawkish sentiments in the West, often leaving governments in a dilemma.

Some, like Australia, have tried to protect themselves with fresh foreign interference laws that criminalise individuals deemed to be meddling in domestic affairs. In 2020, the US imposed visa restrictions on people seen as active in UFWD activities.

An irked Beijing has warned that such laws – and the prosecutions they have spurred – hinder bilateral relations.

“The so-called allegations of Chinese espionage are utterly absurd,” a foreign ministry spokesperson told reporters on Tuesday in response to a question about Yang. “The development of China-UK relations serves the common interests of both countries.”

Some experts say that the long arm of China’s United Front is indeed concerning.

“Western governments now need to be less naive about China’s United Front work and take it as a serious threat not only to national security but also to the safety and freedom of many ethnic Chinese citizens,” Dr Hung says.

But, he adds, “governments also need to be vigilant against anti-Chinese racism and work hard to build trust and co-operation with ethnic Chinese communities in countering the threat together.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLast December, Di Sanh Duong, a Vietnam-born ethnic Chinese community leader in Australia, was convicted of planning foreign interference for trying to cosy up to an Australian minister. Prosecutors argued that he was an “ideal target” for the UFWD because he had run for office in the 1990s and boasted ties with Chinese officials.

Duong’s trial had centred around what he meant when he said the inclusion of the minister at a charity event would be beneficial to “us Chinese” – did he mean the Chinese community in Australia, or mainland China?

In the end, Duong’s conviction – and a prison sentence – raised serious concerns that such broad anti-espionage laws and prosecutions can easily become weapons for targeting ethnic Chinese people.

“It’s important to remember that not everyone who is ethnically Chinese is a supporter of the Chinese Communist Party. And not everyone who is involved in these diaspora organisations is driven by fervent loyalty to China,” Dr Wong says.

“Overly aggressive policies based on racial profiling will only legitimise the Chinese government’s propaganda that ethnic Chinese are not welcome and end up pushing diaspora communities further into Beijing’s arms.”