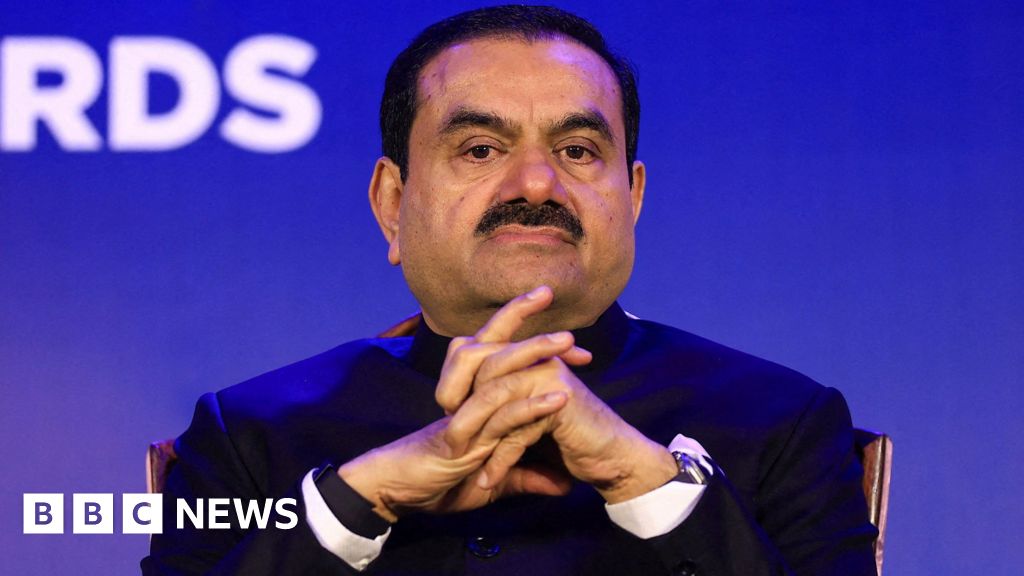

Reuters

ReutersBribery charges by a US court against the Adani Group are unlikely to significantly upset India’s clean energy goals, industry leaders have told the BBC.

Delhi has pledged to source half of its energy needs or 500 gigawatts (GW) of electricity from renewable sources by 2032, key to global efforts to combat climate change.

The Adani Group is slated to contribute to a tenth of that capacity.

The legal troubles in the US could temporarily delay the group’s expansion plans but will not affect the government’s overall targets, analysts say.

India has made impressive strides in building clean energy infrastructure over the last decade.

The country is growing at the “fastest rate among major economies” in adding renewables capacity, according to the International Energy Agency.

Installed clean energy capacity has grown five-fold, with some 45% of the country’s power-generation capacity – of nearly 200GW – coming from non-fossil fuel sources.

Charges against the Adani Group – crucial to India’s clean energy ambitions – are “like a passing dark cloud”, and will not meaningfully impact this momentum, a former CEO of a rival firm said, wanting to remain anonymous.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGautam Adani has vowed to invest $100bn (£78.3bn) in India’s energy transition. Its green energy arm is the country’s largest renewable energy company, producing nearly 11GW of clean energy through a diverse portfolio of wind and solar projects.

Adani has a target to scale that to 50GW BY 2030, which will make up nearly 10% of the country’s own installed capacity.

Over half of that, or 30GW, will be produced at Khavda, in the western Indian state of Gujarat. It is the world’s biggest clean energy plant, touted to be five times the size of Paris and the centrepiece in Adani’s renewables crown.

But Khavda and Adani’s other renewables facilities are now at the very centre of the charges filed by US prosecutors – they allege that the company won contracts to supply power to state distribution companies from these facilities, in exchange for bribes to Indian officials. The group has denied this.

But the fallout at the company level is already visible.

When the indictment became public, Adani Green Energy immediately cancelled a $600m bond offering in the US.

France’s TotalEnergies, which owns 20% of Adani Green Energy and has a joint venture to develop several renewables projects with the conglomerate, said it will halt fresh capital infusion into the company.

Major credit ratings agencies – Moody’s, Fitch and S&P – have since changed their outlook on Adani group companies, including Adani Green Energy, to negative. This will impact the company’s capacity to access funds and make it more expensive to raise capital.

Analysts have also raised concerns about Adani Green Energy’s ability to refinance its debt, as international lenders grow weary of adding exposure to the group.

Global lenders like Jeffries and Barclays are already said to be reviewing their ties with Adani even as the group’s reliance on global banks and international and local bond issues for long-term debt has grown from barely 14% in financial year 2016 to nearly 60% as of date, according to a note from Bernstein.

Japanese brokerage Nomura says new financing might dry up in the short term but should “gradually resume in the long term”. Meanwhile, Japanese banks like MUFG, SMBC, Mizuho are likely to continue their relationship with the group.

The “reputational and sentimental impact” will fade away in a few months, as Adani is building “solid, strategic assets and creating long-term value”, the unnamed CEO said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA spokesperson for the Adani Group told the BBC that it was “committed to its 2030 targets and confident of delivering 50 GW of renewable energy capacity”.

Adani stocks have recovered sharply from the lows they hit post the US court indictment.

Some analysts told the BBC that a possible slowdown in funding for Adani could in fact end up benefitting its competitors.

While Adani’s financial influence has allowed it to rapidly expand in the sector, its competitors such as Tata Power, Goldman Sachs-backed ReNew Power, Greenko and state-run NTPC Ltd are also significantly ramping up manufacturing and generation capacity.

“It’s not that Adani is a green energy champion. It is a big player that has walked both sides of the street, being the biggest private developer of coal plants in the world,” said Tim Buckley, director at Climate Energy Finance.

A large entity, “perceived to be corrupt” possibly slowing its expansion, could mean “more money will start flowing into other green energy companies”, he said.

According to Vibhuti Garg, South Asia director at Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), market fundamentals also continue to remain strong with demand for renewable energy outpacing supply in India – which is likely to keep the appetite for big investments intact.

What could in fact slow the pace of India’s clean energy ambitions is its own bureaucracy.

“Companies we track are very upbeat. Finance isn’t a problem for them. If anything, it is state-level regulations that act as a kind of deterrent,” says Ms Garg.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMost state-run power distribution companies continue to face financial constraints, opting for cheaper fossil fuels, while dragging their feet on signing purchase agreements.

According to Reuters, the controversial tender won by Adani was the first major contract issued by state-run Solar Energy Corp of India (SECI) without a guaranteed purchase agreement from distributors.

SECI’s chairman told Reuters that there are 30GW of operational green energy projects in the market without buyers.

Experts say the 8GW solar contract at the heart of Adani’s US indictment also sheds light on the messy tendering process, which required solar power generation companies to manufacture modules as well – limiting the number of bidders and leading to higher power costs.

The court indictment will certainly lead to a “tightening of bidding and tendering rules”, says Ms Garg.

A cleaner tendering process that lowers risks both for developers and investors will be important going ahead, agrees Mr Buckley.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.